The Asian-American narrative is hard to write because so much of it exists in silence— Jeanelle Fu, Blueprints1

The recent mass shootings in Monterey Park and Half Moon Bay were yet new cases of violence against Asian Americans. When a gunman opened fire at a Lunar New Year celebration in Monterey Park, killing eleven and wounding nine, mourning and anger raged across Asian American communities. But two days later, while many were still grieving the Monterey Park shooting, another gunman murdered seven farmworkers and critically injured one other at two farms in the Half Moon Bay area. Indeed, anti-Asian hate crimes have been significantly on the rise since the pandemic started in 2020, but these recent California mass shootings joined the list as some of the deadliest attacks against Asian Americans in recent years.2

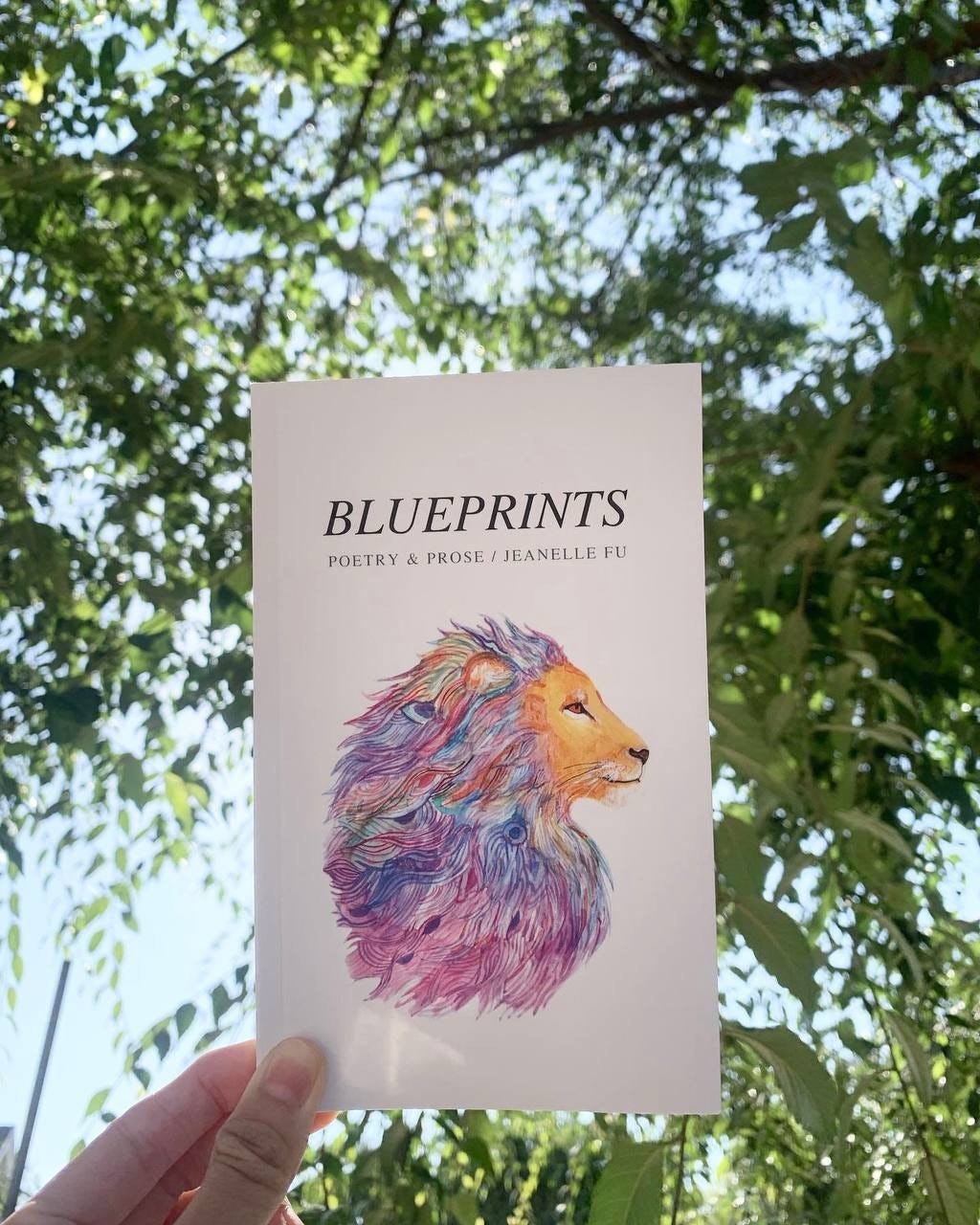

It is clear to see how Asian American grief is a central theme of Jeanelle Fu’s poetry collection, Blueprints. The opening pages of the book introduce us to the story of her grandfather, who immigrated as a refugee from China with two million others to begin a new life in the United States. From there, Fu writes about the sweat and tears her progenitors toiled as immigrants in a foreign land to provide a secure and safe future for their children.

For Fu, Asian American existence is lived in-between. Millions upon millions of immigrants from Asia have immigrated to the United States over the years in order to build better futures for their children or provide for their families back home. Many of them are escaping famines and droughts, genocides and political oppression, traversing many seas and oceans to pursue better opportunities in the United States. Indeed, this is Fu’s story of how her family became Asian American, writing:3

I am a child of exodus held intricately by bonds of sacrifice I am the daughter of an architect who laid out a blueprint of my life, with sweat and tears

For many Asian Americans like Fu, this immigration history has created a kind of homesickness, as many have struggled to build homes in a foreign land where anti-Asian violence continues to run rampant. Silenced by different powers and principalities of racialization, Asian Americans have been historically forced into stereotypes that engendered their unbelonging. Whether as “model minorities” or “perpetual foreigners,” Asian American life has been defined by their marginalization — estranged from their homelands in Asia, and never belonging in their new “homes” in America.

My friend

, who is an Indian American theologian, explains succinctly the racialization and marginalization of Asian Americans in his Substack newsletter:I frame this response within the ongoing, persistent mythology of Asians as model minorities and perpetual foreigners. As model minorities, Asians are upheld as upwardly mobile, eager-to-be-assimilated immigrants. Following the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act, it was engineers, doctors, scientists, and scholars who were allowed entry into America. In return, white politicians, social commentators, sociologists, and more used this to contrast Asians directly with the ongoing racist perceptions of Black folk as criminal, lazy, and prone to violence. However, Asians ought not understand their utility and tokenization as a safety net. As the COVID pandemic has revealed, Asians today continue to be imagined as a perpetual foreign “other” that carries mysterious languages and diseases with them. For all our attempts at assimilation and integration into society, we will always be “other.”4

Amar later contends that this marginalization is unjust. He writes that Asian American identity does not have to be defined by the “persistent mythology of Asians as model minorities and perpetual foreigners.” Indeed, Asians do not have to be marginalized and racialized in order to become “American”:

I am unwilling (and frankly, unable) to give up my Indianness in order to fully participate in a project aimed towards uniting our communities and nation. This is because any appeal to unity that comes at this cost is not actually a call to unity, it is a call to homogenization.5

I completely agree with Amar that Asian American identity does not have to be defined by racism and marginalization.

In Blueprints, Fu sketches a portrait of Asian America that is a beautiful tapestry stitched with joy, grief, beauty, and faith. Fu imagines new possibilities for Asian American life that is no longer bound to the racialized logics of exclusion, which for her is disrupted by the existence of Jesus the Nazarene — who is God with us not only in our triumphs but precisely in our grief:6

Jesus walked this earth displaced, a dark-skinned refugee Not a stranger to those in mourning called the man of sorrows God buried death and laid his body down like the beaten path to a new homeland

Who Fu imagines is a God who decentered Godself to be with us, a God who condescended in the body and blood of Jesus — the displaced, dark-skinned refugee. In Jesus’ body, Fu looks up and finds her hope. She sees her Asian American story entangled and belonging to God’s story, where she imagines her life as wrapped up in the God who died on a cross to save the world:7

when tears fall unseen and wounds bloom in silence I'll kneel at the foot of the Cross and remember the crown of thorns you wore for me

In Chung Hyun Kyung’s Struggle to be the Sun Again: Introducing Asian Women’s Theology, Kyung argues that Asian American theology is created through storytelling. The narratives we encounter in the Scriptures are filled with stories — stories that re-orient our minds and hearts toward newness of life, or eternal life as Jesus describes. It all begins with stories.

It is a tragic injustice when our stories are forcibly silenced or erased (as felt through the recent mass shootings). Such is the case with the stories of Asian America, as Fu accurately reflects, “The Asian-American narrative is hard to write / because so much of it exists in silence.”8 Yes, our stories have been forced to the margins of theological, public, and political discourse in America. As we are called “model minorities” and/or “perpetual foreigners,” Asian Americans are expected to go with the flow and let their stories dissipate into oblivion.

But, like Fu, I believe that Asian American identity is at the cusp of a different meaning — a re-orientation away from exclusion and silence, as it moves toward belonging and healing. Asian American identity does not have to be defined by the marginalization of stereotypes and racialized exclusion. Asian American identity can be something different… because it is something different.

Indeed, Asian American identity is a beauty to behold, a reality to be celebrated. We can show the world that our Asian American stories ought to be treasured and valued, not disposed of or excluded. Fu's poetry reminds me that our stories can be heard and healed as we belong to one another in deep compassion. Thus, we need to share our stories without fear of shame, as protest against the forces of exclusion and death — as the beginning of a life lived together:9

don’t hide your pain... my heart lay bare we need each other to articulate the heaviness within

Jeanelle Fu, Blueprints: Poetry and Prose (Self-Published), 18.

10,905 cases of anti-Asian hate crimes and acts of discrimination were recorded by Stop AAPI Hate between 2020 and 2021.

Fu, 5.

Amar Peterman, “at what cost? when unity isn't worth it,” in

.Ibid.

Fu, 77. Emphasis added,

Fu, 48.

Fu, 18. Emphasis added.

Ful, 80, 83. Emphasis added.